I recently visited Underley Hall near Kirby Lonsdale in Cumbria with Richard Brook of Manchester School of Architecture. This is Richard’s account of the visit:

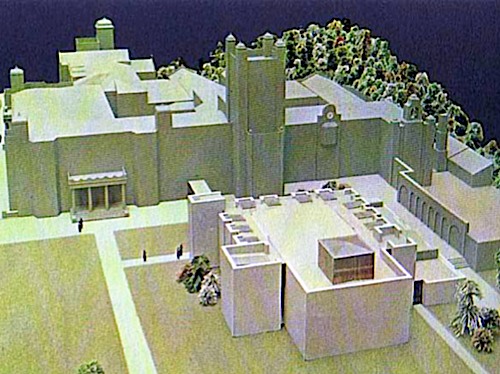

Architects’ original model of the proposed Chapel at Underley Hall

Representatives of CiA and team-bau recently made a foray into Cumbria to investigate a little known chapel by BDP, built between 1964 and ’66 and annexed to a country mansion. The chapel was commissioned by the Lancaster diocese shortly after they took ownership in 1959 to run the estate as a junior seminary for the training of Catholic priests: St. Michael’s. Nikolas Pevsner in 1968 described the chapel as “easily the best recent ecclesiastical building in the countryâ€. The site is now a residential school for young people with behavioural problems and as such may only be accessed by prior arrangement.

The principal building on the estate is the rather imposing Underley Hall, built over the footprint of a former house within an estate established since the Sixteenth Century. It was constructed after 1825 in a Jacobean Revival style for Alexander Nowell and designed by George Webster (see Notes at the foot of this post).

Drawing by Thomas Allom, engraved by J Thomas, 1830.

http://www.geog.port.ac.uk/webmap/thelakes/html/lgaz/lk12046.htm

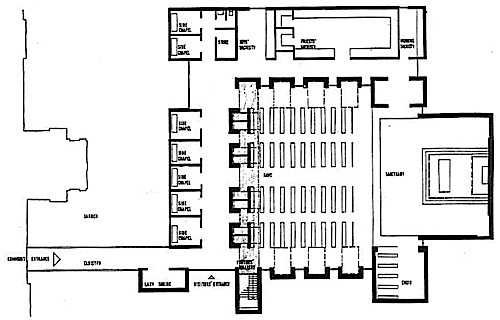

Plan from Architecture North West. No.33, p.15, 1968

The 1960’s chapel sits to the east of the main hall, between it and the River Lune and was designed by William (Bill) White and John Sheridon, assisted by a full compliment of consultants from the progressive multi-disciplinary office of Building Design Partnership in Preston. A Victorian palm house was demolished to make way for the new addition.

The planning of the scheme and the distinctive cellular nature of its elements were informed by both designated programme and material selection. The demand for more side chapels than would be requisite in a parish church, delivered a strip of seven cells for private contemplative prayer to the rear of the main space. These can be accessed with no interruption to services and are subtly composed to reinforce solitude and composure. A mixture of long windows or roof lanterns either facilitate connection or separation from external stimuli, and a single step up within each chapel further promotes the isolative qualities of these spaces.

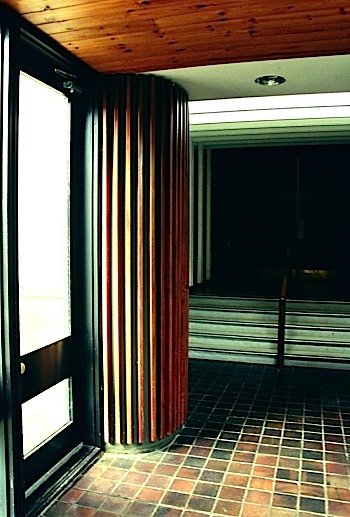

Budgetary restrictions meant that the material palette, whilst restrained does not bear the quality hallmarks of the building’s composition. Both the internal and external walls are constructed of concrete paving “split to reveal the colour and texture of the natural aggregateâ€. It was intended that this was complimentary to the stone of the existing hall, though perhaps a crisper, more reflective masonry would have provided a vivid but restrained contrast. The settling and movement properties of the concrete were effectively unknown and lead to the repeating ‘C’ shaped bays separated by full height windows. The floor is finished throughout in quarry tiles and fittings and linings are almost exclusively in stained softwood.

Most of the original fabric remains intact, though the sanctuary and nave spaces have been subdivided with temporary partitions into a store and gymnasium respectively. The simple confessionals, which sat beneath the visitor’s gallery, have also been dismantled. The roof construction is cleverly afforded an airy presence by the use of lanterns that occupy the spaces between the deep trusses and cast a soft light to the side and rear walls. Above the Sanctuary is another huge roof lantern that would have undoubtedly drawn focus to the altar. Externally this is expressed as a rather squat slate-hung tower.

The connection to the existing hall is by a glazed corridor, described as a cloister, but not perhaps evoking the monastic spirit that one would traditionally associate with the term. Where the new and old meet, it is, however, a neat junction composed of cleanly engineered timber components that visually frame and stretch the event of threshold transition.

An element of the scheme unknown to either of the visiting parties was waiting beyond the breadth of a corridor, once inside the original building. Contemporary to the chapel was a small dining room created from the infill of an internal courtyard. The space had been recently stripped back to reveal that all of the finishes were intact, original wall and floor linings and a beautifully engineered truss system, composed of slender timber sections and tension rods to facilitate a continuous band of clerestory glazing and carry a roof lantern. The quality of the diffused light even on such a grey day was soft and calming and the muted palette of the rest of the fittings gave the space an appropriately ethereal time capsule quality.

A quick sojourn across the playing fields for a more distant contextual appreciation revealed two things; one, that the light that day was particularly bad for photography and two, that our initial sentiment, with regard the lack of contrast between the old and the new buildings, was somehow proven. The lack of a powerful direct light source didn’t permit the formal interplay that shadow would promote in the reading of the two forms and perhaps would justify a material with stronger reflective characteristics.

One final surprise still lay in store, a Waring and Gillow table with a ‘new’ Formica top. Considerably more jarring a collision than any intervention by BDP.

All text and photographs copyright Richard Brook 2009

Notes

“1825 15 January. The foundation stone of the new Underley Hall was laid a few days ago by the owner Alexander Nowell, esq. It is nearly on the site of the old house and Mr. Webster of Kendal is the architect.â€

From: ‘Supplementary Records: Kirkby Lonsdale’, Records relating to the Barony of Kendale: volume 3 (1926), pp. 278-291. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=49383

“Born in 1797 George Webster was the son of mason turned architect Francis Webster of Kendal. In 1818, at the age of 21, George Webster designed his first independent country house, Read Hall in Lancashire and work commenced on his design for Underley Hall in 1825.†http://www.whittingtonvillage.fsnet.co.uk/html_pages/whittington_hall/whittington_hall.html

see also: Taylor, A., The Websters of Kendal, Cumberland + Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, 2004. ed. Martin, J.

I am honoured to officially invite you to participate “The Eleventh Banquet of Iran Architectural Blogs” with the topic of “Professional Ethics in Architecture and Urbanism”, and will be grateful if you can send me your thoughts/comments/papers (about topic) as links until this month to this address: hesameshghi@hotmail.com

Hope to see you soon in the 11th symposium!

With warm regards.

Hesam Eshghi Sanati

http://www.hesameshghi.persianblog.ir

More pictures of Underley hall Chapel and refectory

http://www.flickr.com/photos/stoneroberts/sets/72157616505879259/

Pingback: CONTINUITY IN ARCHITECTURE » Blog Archive » It’s dark. Dark in the daytime.