“Preston has a picturesqueness of outline and a suggestion of spaciousness from a distance which distinguish it from most Lancashire cotton towns.â€1

The Twenty-First Century city is a combination of two different ideas; the traditional city of streets and squares, and the modern city of isolated elements surrounded by parkland. The traditional city is really composed of spaces, which are lined with buildings. So, for example, the primary street within an urban environment is a long thin space through which people travel, which is bounded by structures that face onto this space. The shapes of the buildings are somewhat deformed to accommodate the pure nature of the street, and thus it is the space which is the predominate element of the composition. The city-in-the-park is the opposite; isolated buildings set with open land, thus emphasising the building rather than the space, which just surrounds the structures in an ill-defined manner.

Preston, a small provincial city in the north west of England is no exception; it has evolved into this awkward mixture of the traditional and the modern. Neither situation really responds or compliments the other, and so the city has grown into a collection of individual structures and spaces.

Preston is well positioned on a ridge above the flood-planes of the River Ribble. This line or edge, known as Fishergate, is part of pre-Roman route which crossed the country, and intersects at the Flag Market square, with a north-south track, Friargate, which was formed by its connection with the lowest crossing point of the Ribble. The Minster marks the eastern end of the city centre, while the train station is positioned at the western point and Fishergate is stretched between them. Close to the Minster are the open Flag Market, the Harris Art Gallery, the Victorian cast-iron covered markets and the Town Hall. These civic elements are testament to the wealth of the city.

In some respects it is a typical industrial city, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries brought massive expansion, and by 1867 it possessed seventy factories. This rapid development destroyed many of the mediaeval structures, but the pattern of the city centre, to the most part, was retained. Indeed, many of the small streets or weinds to the south of Fishergate reflect the pre-industrial routes and field patterns.

The “marvellously brutalâ€2 Bus Station was constructed to the north-east of the Town-hall and the markets. The area was at the time densely occupied with mills and terraced houses. The building is situated a couple of blocks from the Townhall, but is very simply parallel to it and therefore to Friargate. It is placed within an open expanse or concourse, which was designed to allow the buses to flow freely around the building. Pedestrians were separated from the traffic with distinct unground routes. It is an enormous and elegant 171 meters long (560ft, it is, after all, a pre-decimalisation building), and can quite fairly be described as a landmark, and therefore an important element within the collective memory of the city. When constructed it paid little heed to pattern of pattern of the place, but has become a well-loved element within the bricolage of Preston. “Some ideal forms can exist as fragments, “collaged†into an empirical environment…â€3

It is obvious that its position within the city doesn’t work. The Bus Station is essentially cut-off from the centre by the Guild Hall, the St. John’s Shopping centre and the concourse itself. The relationship with Church Street is lamentable, in fact, this area of the city, which was once thriving and profitable, has become, in places, derelict. The ring road has exacerbated the problems; effectively cutting the north of the city from the centre, and thus the land to the east, beyond the Bus Station, is almost inaccessible. This is not something new, it was actually foreseen by Derek Linstrum in his mostly ecstatic 1969 review of the building: …“the failure to estimate the building’s potential as an important addition to the town’s social life.â€4

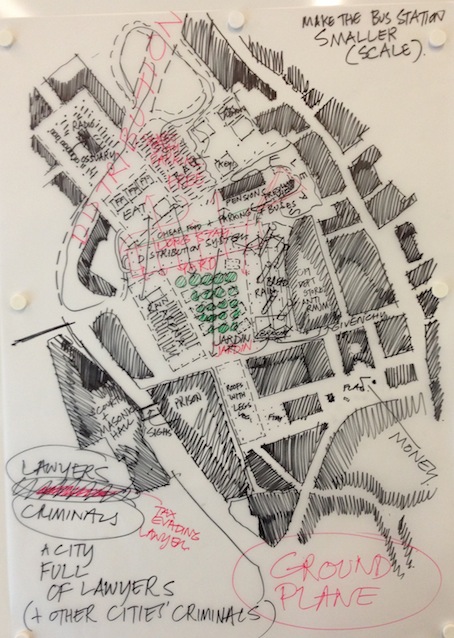

Gate 81 is a series of projects that intends to raise the profile of the building, and therefore increase the chance of saving it from the intended demolition. The latest project was a one-day charrette hosted by BDP Architects, ironically the architects of the original building and the now-abandoned Tithebarn shopping centre that was intended to replace the building. Academics, and students from the schools of architecture in Manchester, Liverpool and Central Lancashire, as well as professional architects and designers attended the charrette. BDP’s chairman David Cash, who quite romantically remembered the time that BDP was still in Preston and the legacy of the George Grenfell-Baines, launched the event. Kevin Rhowbotham delivered the key-note talk, well, call-to-arms. He invoked the memory of Collage City and pressed us all to consider the dialectical opposition of the Object and the Field, and how each can distinguish the other.

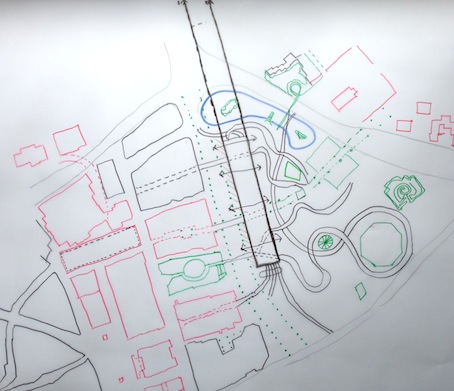

Five groups were created, each contained a mixture of professionals and students, and each approached the problem of how to revitalise this area of the city of Preston in a distinct and individual way. However, what linked all of the proposals was the appreciation that the project is much larger than just the remodelling of the Bus Station; it is an Urban Regeneration problem. All of the proposals considered the link between the city centre and the building, the  hinterland to the east and relationships that exist between the key elements of the urban environment.

“As in a cubist painting, where the organisational geometries do not reside in the objects themselves, the possibilities of combining various buildings within a system of order which attributes to each piece a bit of the organisation becomes almost infinite.â€5

Group 1: Undivided

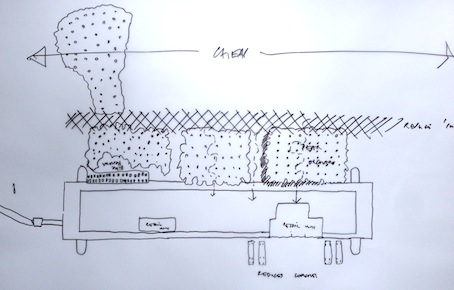

Preston Bus Station is shelter-like structure elevated upon strong concrete legs; this evokes comparisons with the cast-iron covered markets. This group proposed to raze the low quality structures directly next to the Bus Station concourse and thus create physical connections between all of the “roofs with legsâ€. The resultant public space or garden could support communal activities and also encourage public movement through the now open structure of the Bus Station, into the more formal area of distribution between the building and the Ring Road

Group 2: The Urban Arboretum Project

Preston’s Indoor Market is situated within a dark and somewhat isolated building, squashed beneath a carpark next to the Ringroad. This group considered the Bus Station as a perfect venue for the new market; it would be easily accessible and very easy to support. The areas behind the building could accommodate allotments and market gardens, while the concourse could hold performances and other communal activities. The top floor of the building also offers opportunities for growing stuff. The element of time and evolution was an important aspect of this project.

Group 3: 50 – 50 Group

This group considered the possibility of creating a direct link between the city’s cultural buildings and the Bus Station. By removing the substandard structures next to the concourse, a vista or connection could be established. This combined with moving all of the bus movement to the rear or east side of the building would create a collection of public spaces that could naturally evolve from temporary to permanent use over the course of a couple of decades.

Group 4: Going Underground

People need a reason to visit a place and therefore this group asked what Preston City Centre was missing. It is widely acknowledged that most casual city-centre shoppers follow a distinct circular route around the shops. If this circuit included a substantial flagship department store to the east of the Bus Station, that is the non-city centre side, then shoppers would be actively dragged through the building en-route. This would act to invigorate the building and any activities would naturally evolve within it.

Group 5: Artefact Park

Preston Bus Station is dramatic symbol of the city. When seen from the ring road it appears as a substantial and protective wall. This group considered the effect that extending the building would have upon the urban environment. To the north, it would recreate the connections that have been lost by the intrusion of dual carriageway, and to the south, relationships could be re-established with Church Street. The area of land to the east, beyond the massive wall could be considered as a garden of lost memorabilia.

1, Derek Linstrum, AJ 6th May 1970. 2, Clare Hartwell and Nikolaus Pevsner, Lancashire North. 3, Thomas Schumacher, Urban Ideals and Deformations. 4, Derek Linstrum, AJ 6th May 1970. 5, Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, Collage City