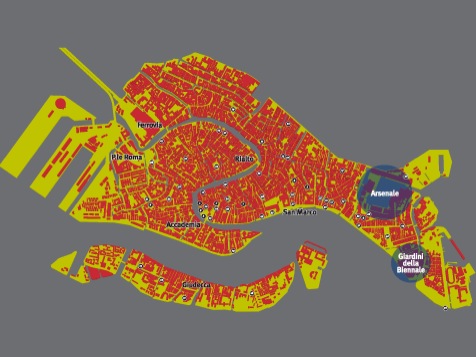

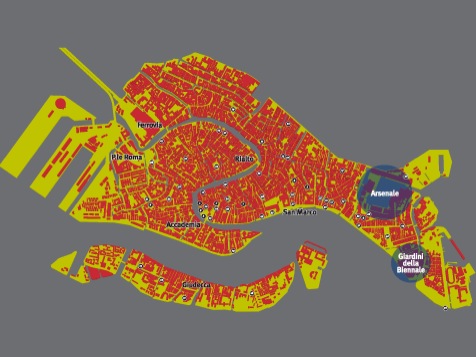

The vast exhibition of contemporary architecture which is the Venice Biennale (curated by Aaron Betsky) opened last weekend in a stormy atmosphere which made the exhibitions oases of rather damp calm, despite the unsettling, luxurious aspirations of some of the exhibitors. How nature, not to mention the current economic storms, intrudes on the best laid plans! The utopian visions of the digital future and interactive environments with new fluid forms are presented in a stunning display at the Arsenale. Marked by a particularly stimulating entrance area (Rockwell Group with Jones/Kroloff) that sets a high standard which the subsequent sequence of displays extend in a series of varied rooms. Much of this material is not new (either in ideas or forms), but is presented here as a spatial experience which tantalises the visitor with possible worlds. The indulgence of the creators in focusing on their own concerns betrays the self-referential interest of much of this work. The MVRDV/Philippe Rahm section for example, with its futuristic urban animation, relaxing naked people and musician improvising on a saw suggests nothing more than the continuing polarity between attention seeking techno-geekiness and a late revival of hippiedom, ideas first synthesised forty years ago by Superstudio.

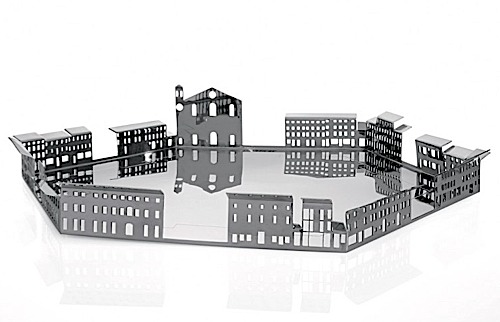

The displays have a strongly historicist feel, with some of the original characters, represented especially by Coop Himmelblau, expanding on their ideas for interactive autonomous environments. The Roma Interrotta exhibition of 1978 is revived as an antechamber to a display of contemporary ideas for Rome, Uneternal City, which takes the earlier urban speculation forward. The other developments of that era are acknowledged in the Italian Pavilion at the Giardini with exhibitions of Madelon Vriesendorp’s provocative images for OMA, Zaha Hadid’s early models and paintings and various works from the office archive of Frank Gehry. The form-laden nature of this work sits somewhat uncomfortably with a series of displays which deal with the social and ecological aspects of contemporary concern, but then in totality the exhibition seems to tip the hat quite frequently to once-were-deconstructivists, as if in memory of Betsky’s own involvement in defining that movement.

The British Pavilion presents a series of housing projects, solid buildings ill-served by the the witlessness of the display. dRMM’s work in particular suffers from the miserable position their models occupy. Contrast this unappealing tightness with the engaging generosity of the French Pavilion, which has pivoting models encouraging engagement from the exhibition visitors, and the German Pavilion’s reassuringly ‘chaotic’ ecological display.

The real surprises within the many varied displays are perhaps best summarised by the Mexican contribution at the Arsenale which provides some welcome social content in distinction to the overwhelmingly form driven displays there. At the Giardini the USA Pavilion provides a cooler response to similar issues, a development which can only be welcomed.

As always the Nordic Pavilion hovers elegantly at the centre of the Giardini. This year it presents a monographic exhibition on the work of the pavilion’s architect Sverre Fehn which in its tranquil confidence provides reassurance that all novelties in architecture eventually pass away…