Our colleague James Robertson continues his doctoral research on Jack Coia with a presentation on his work at the Association of Art Historians Summer Symposium at the Henry Moore Institute (24-25 June 2010) in Leeds. The conference theme is ‘Architectural Objects:Discussing Spatial Form across Art Histories’, and James’s abstract is below.

The Prototype Pavilion – Modernism, National Identity and Religion in the Context of Scotland

The national and international architectural expositions of the twentieth century gave designers the opportunity to craft on a small scale, with very distilled and often experimental forms of architecture. Through their participation in such varied architectural displays, designers would very often create work which in some way reflected the ‘mood’ of the nation or of the era. One such exposition, the international importance of which has not yet been satisfactorily documented, was the Glasgow Empire Exhibition of 1938.

A team of Scottish architects was commissioned to design the exposition pavilions representing industry and institution, in a nationally symbolic gesture of optimism following decades of economic and social depression. The pavilion of the Roman Catholic Church, designed by the Glasgow architectural practice of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, headed by the Scoto-Italian Jack Coia (1898-1981), was one of the most striking, unconventional and overtly ‘modern’ pavilions created at the exposition, particularly in a religious context, and in fact could be said to be seminal in terms of modernism in Scotland in a wider sense[1].

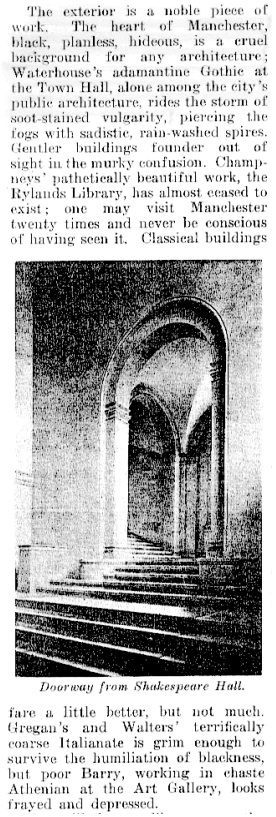

In collaboration with artist colleagues and student apprentices, and looking simultaneously to Scotland’s national past and to international architectural developments, Coia fused artistic and architectural themes with a provenance in contemporary Italian architectural projects. The de Chirico-influenced metaphysical painting of churches such as San Felice da Cantalice, Rome (Paniconi & Pediconi, 1934) and the political montages of the ‘Fascist’ architecture of the time, such as Terragni’s Casa del Fascio, Como (1932), are critically apparent, as are the quasi-religious architectural devices of the Exposition of the Fascist Revolution, Rome (1932). Coia effectively experimented on a small scale with architectural motifs at Empirex[2] which would subsequently evolve into the ‘architectural objects’ of much of the firm’s later, more celebrated work.

It can be argued that that Empirex allowed Scotland to experiment with, through the medium of a small-scale pavilion in a national exposition, and through Coia, the prototype for a Scottish national version of ecclesiastical modernism, with potentially direct connections to Rome, the Vatican and the Italian artistic and architectural milieu of the era.

[1] The Scottish Catholic historian, Peter Anson argued in 1939 that the pavilion ‘may mark the beginning of a new epoch in Scottish church architecture’

[2] Empirex was an acronym relating to the Glasgow Empire Exhibition