Ph.D. candidate James Robertson is continuing his research into the early career of Jack Coia and has recently visited both the Sir Basil Spence exhibition in Edinburgh: Back to the Future (Dean Gallery, Edinburgh), and the Gillespie, Kidd & Coia exhibiton in Glasgow: Gillespie, Kidd & Coia: Architecture 1956-1987 (The Lighthouse, Glasgow). James writes

“The recently opened Gillespie, Kidd & Coia exhibition, based at the Lighthouse Centre in Glasgow, is essentially a showcase for the architectural careers of Isi Metzstein and Andy MacMillan. Whilst it is an informative expose of their contribution to the architectural output of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, its great fault is that it fails to contextualise their work, and attributes apparently little to the heritage of the firm, barely acknowledging Jack Coia himself. In a small, barely noticeable newspaper cutting, Jack Coia talks of the “collective personality†of his office (referring to the atelier ethos, where student and professional alike were permitted to contribute freely to the architectural discourse surrounding office projects). It is ironic how this ethos has been subverted or even dismissed.

The exhibition starts, in 1956, with St. Paul’s, Glenrothes, hailed as a seminal building in terms of Modernism in Scotland, with Metzstein and MacMillan apparently breaking the ecclesiastical mould of the firm. As Johnny Rodger highlights in his contribution to the catalogue which accompanies the exhibition, Gillespie, Kidd and Coia had produced churches which had been viewed as very much “of their timeâ€. The younger architects’ unsentimental, rational approach may be obvious and even pioneering in terms of ecclesiastical “styleâ€, but to what extent were “their†churches based on genuine liturgical and social functions, and not on the “whole rag-bag of contemporary cliches†so abhorred by Peter Hammond in his contribution to Modernism and the Architecture of the Church.

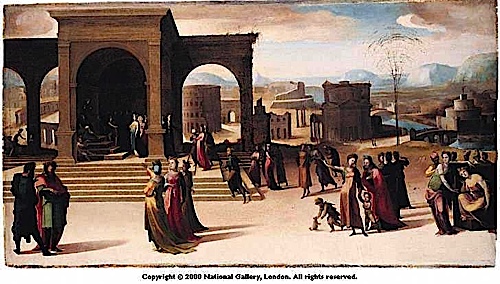

The question of whether a church should be recognisably a church or whether Modernist principles should dictate its appearance is pertinent when considering 20th century ecclesiastical design. Coia’s contemporary, Sir Basil Spence, of course famously re-designed Coventry Cathedral following its Second World War destruction. Charles McKean describes Coventry as a “box for Arts and Craftsâ€, and as picturesque in its setting. This appreciation or concern for context is also recognisable in Coia’s early churches, their Italianate expressiveness “cutting a dash in the landscapeâ€. However, Hammond, in his critique of the modern church, dismisses Coventry Cathedral as merely pandering to visual effect in its rather “pictorial†or “romantic†conception.

An early chance to compare Coia and Spence was provided by their participation in the 1938 Glasgow Empire Exhibition. Coia’s Roman Catholic Pavilion and Palace of Industries North were both at odds with his initial work since becoming principal of the Gillespie, Kidd and Coia practice in 1927, having both been designed along decidedly Modernist lines. In contrast Spence offered something more traditional in his House for the Council of Art and Industry. Against this conservative approach, this difference suggests that at that stage in their early careers Coia was so gifted and comfortable with the concerns of particular clients that he was able to literally decide on the correct or appropriate course of design according to the given situation (in some cases, such as at the 1938 Exhibition, more or less pleasing himself within certain predetermined guidelines, which were largely to do with construction technique and timescales). This idea also resonates with Coia’s popularity amongst his students: if he was not believed to have been a truly modern thinker and designer, with this emphasis later seemingly conferred on Metzstein and MacMillan, why was he so popular and well remembered by his students? He must necessarily have been conversant with architectural progress and advancement to so inspire his students. Indeed, on Thomas Warnett Kennedy’s first meeting with Coia, he declared that his “own imagination lit up like a lampâ€.

One of the fundamental problems of the school of thought that places Metzstein and MacMillan at the creative helm of the firm, post-1956, is that both Coia’s name and that of the firm appear on more modern buildings than Metzstein and MacMillan are perhaps prepared to admit. The authorship of drawings, therefore, creates an ambiguity over the (currently one-sided) intellectual ownership of the Glasgow firm’s architectural output and indeed the relative reputations of Coia and the more professionally successful Spence.â€

Basil Spence & the Coventry Cathedral model

Basil Spence

The Lighthouse, Glasgow