September 2007 marks ten years since the death of Aldo Rossi.

The continuous process of urban history was a theme which was developed in Rossi’s The Architecture of the City. Published in Italian in 1966 and translated into English in 1982, the book presented a tough critique of the modernist city, but used marxism to argue for an almost fatalistic adherence to the zeitgeist. Rossi proposed that architecture stood outside the fluid tide of history, dependent for its power on the qualities of its geometry and accumulation of patina through its survival over time. This placed great emphasis on the collective experience of the city, and consequently reduced the individualising tendencies of the unique monument, creating a significant focus in this analysis on the issue of permanence in architectural typology. Rossi’s text distinguished surface appearance from context, the atmosphere of a city being apparently replicable without any comprehension of the typology from which it was built, although this division would be a phenomenon which would bedevil the broader reception of his own work that was decades in the future. Mistrustful of the subjectivity of proponents of contextualism, his rationalism sought an architecture and urbanism which was less apologetic about its presence, but which acknowledged that time would transform it, that it would, as it were, domesticate the urban intervention through use. The ambiguity of this position in relation to the temporal dimension contrasts with the fixity with which contextualists appropriated a past point in history.

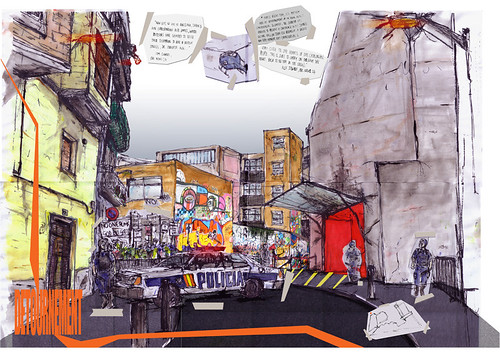

Illustrated is the Piazzetta Croce Rossa, completed by Rossi in 1988, is a small urban space in the centre of Milan, on the major thoroughfare of Via Manzoni, and adjacent to the opening of Via Montenapoleone, and therefore in the middle of what has become the fashion quarter of the city, and one of the most important centres in this global industry, the so called quadrilatero d’ oro, the golden block. The urban space sits above the Montenapoleone Metro station with entries and exits to and from the station disposed around the space, but the centre is focused on a symmetrically arranged space, lined with two rows of trees, benches and street lights. On the axis sits the Monument to Sandro Pertini (named for the President of the Italian Republic 1978-85), in the form of a cubic block faced in the same pink and grey Candoglia marble as is used on the duomo of Milan. Ten metres square the cube is blank on two sides, with the third featuring a bronze clad water spout in the form of an equilateral triangle, with a long horizontal slot in the facade above. The fourth side, which faces towards the opening of Via Montenapoleone, is open and consists of a set of oversized steps up to a viewing platform. The monument’s elements refer to a number of examples of Rossi’s personal iconography, and therefore to his general typological collection of forms as expressed in previous works. So the cube in Milan refers to the cubic sanctuary at the Modena cemetery, and its conjunction with steps within the form to his competition design for the Monument to the Resistance at Cuneo (1962). The triangular fountain was another familiar motif, first used in the courtyard of the De Amicis school at Broni in 1969-70. The oversized steps, as a form of auditorium had been used in the courtyard of the elementary school at Fagnano Olona of 1972. Most users of this space would be unfamiliar with these works, but would be familiar with the conventional, everyday sources in the cityscape from which Rossi himself distilled his preferred forms. The monumental flight of marble steps, however, would be familiar to most Italians as the compositional basis of the Vittorio Emanuele Monument in Rome, the national shrine but also the spectre that haunted the country’s twentieth century architecture. Its offspring sits in miniature in Milan, denuded of its iconography and its steps or seats awaiting the unfolding of a more quotidian urban drama.